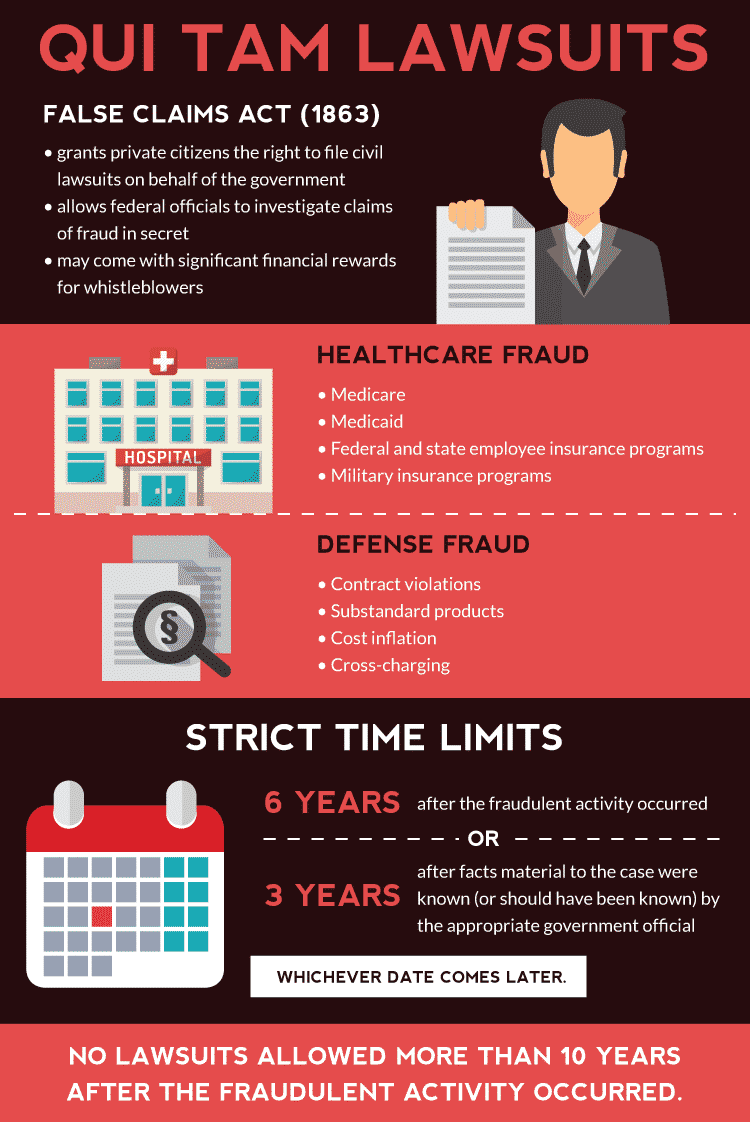

Enacted in 1863, the False Claims Act extends private citizens the right to pursue stolen federal dollars on the government’s behalf. In exchange for their efforts, whistleblowers who take action against fraud can be rewarded with generous settlements.

Our experienced qui tam lawyers have helped numerous whistleblowers step forward with confidence.

Qui tam law encourages private citizens to file civil lawsuits on the government’s behalf, demanding reimbursement for the taxpayer dollars lost to fraud. In exchange for their efforts, and the significant risks involved in blowing the whistle, these “relators” can be rewarded with a percentage of the government’s recovery. They are also protected from retributive acts by one of the nation’s strongest anti-retaliation provisions.

After the Revolution, the Civil War represents the second great debt crisis in our nation’s brief history. Between 1860 and 1865, the national debt soared from around $65 million to $2.76 billion, according to estimates made by Quartz finance writer Matt Amanips.

Increasing revenue was critical. The country’s first income tax was signed into law by Lincoln in 1862 (and repealed a decade later) and tariffs skyrocketed in the North. But nearly two-thirds of the government’s revenue came by selling bonds. By the end of the War, an estimated 5% of the Northern population held government bonds; only 1% had bank accounts at the time.

The government was in hock, with no money left over to fund investigations of fraud or enforcement measures.

The solution, as Congress saw it, was to give private citizens the power to investigate and enforce fraud against the government. With the False Claims Act of 1863, citizens of the United States gained the right to sue fraudsters in civil court on behalf of the federal government. The law’s qui tam provision rewards these relators for their efforts, granting them a percentage of any ultimate financial recovery.

Qui tam is taken from the Latin phrase, qui tam pro domino rege quam pro se ipso in hac parte sequitur, which translates literally to, “he who brings a case on behalf of our lord the King, as well as for himself.”

Today, the False Claims Act continues to supply the government with its primary tool in fighting fraud. Tax fraud is not covered by the False Claims Act, although filing a whistleblower lawsuit may be possible in some states. Securities fraud is handled by the Securities and Exchange Commission. In all of these cases, however, successful relators can secure a portion of the government agency’s award or settlement.

Defense and healthcare fraud are, by far, the most frequent sources of qui tam litigation. After all, the federal government operates the largest health insurer in the country: the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. America also happens to be home to the most expensive military in the world, spending over $824 billion per year to keep the armed services going.

The federal government provides healthcare coverage for more than 100 million people every year, offering essential benefits through Medicare, Medicaid, federal employee insurance programs and military benefit programs. Over $900 billion flow annually from the federal government to healthcare providers, hospitals, long-term care facilities, pharmaceutical companies and medical device manufacturers to keep this system running.

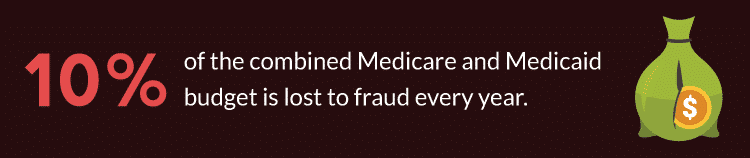

The opportunities for increasing profits, at the expense of patients and taxpayers, are enormous and ever-present. Largely thanks to the work of whistleblowers, billions of dollars in healthcare fraud have already come to light. Yet the Government Accountability Office continues to include Medicare and Medicaid on the agency’s roster of “High Risk” programs, which are particularly vulnerable to fraud, waste and abuse. All signs suggest that healthcare providers and facilities bilk the federal government out of nearly 10% of its annual medical budget.

Common in Medicare and Medicaid fraud cases, kickback arrangements are frequently brokered to induce healthcare providers to purchase more prescription drugs or boost referrals. Certain types of referrals are expressly forbidden by federal law. The Stark Laws, enacted between 1990 and 2007, prohibit “self-referral,” in which a doctor refers their patients to certain medical institutions with which they have a financial relationship.

While any lie on a bill submitted to the government falls under this category, double-billing for medical services, charging Medicare or Medicaid for a more expensive treatment than was actually provided (“upcoding”) and falsifying patient records are particularly common.

Filing claims on behalf of “ghost” patients, who either don’t exist or did not receive the claimed treatment, is a surprisingly frequent form of healthcare fraud.

“Unbundling” services is another major problem. The government often sets a fixed reimbursement scheme for a series of procedures normally provided together. When these services are de-coupled for the purposes of billing, medical providers stand to win higher reimbursement rates.

Pharmaceutical companies often advertise their products for non-approved uses, a violation of federal law that can disproportionately affect Medicare.

Medical institutions and universities that provide the government with false information to secure research funding or violate provisions of a grant can be held liable in a qui tam lawsuit.

Beyond covered medical services, the government usually reimburses hospitals for a portion of their costs and overhead, creating a strong incentive for medical institutions to over-report their numbers.

Government health programs tend to reimburse inpatient medical facilities on a per-patient basis, taking diagnosis, but not length of stay or actual treatment costs, into account.

As a result, sicker patients, who require longer hospital stays and more-costly treatments, can take a deep cut out of a hospital’s profits. Healthier patients with the same diagnosis, on the other hand, can be treated cheaply, allowing the facility to maximize profits. These misaligned incentives encourage hospitals to favor healthy people, at the expense of those in poor health. This practice, known as “red-lining,” is a violation of federal law, and may also constitute a violation of the False Claims Act.

Accurate statistics are hard to find on fraud involving defense contractors, but an internal report from the Pentagon, picked up by The Hill, suggests that between 2001 and 2011 the government lost around $1.1 trillion to fraud and abuse. Defense, after all, is how the False Claims Act got started; Union soldiers discovered that many of their bullets had been filled with sawdust, rather than gunpowder.

Most defense contracts mandate the use of components or products that meet industry specifications for quality. Some contracts also require the use of parts manufactured in the United States, or prohibit the use of refurbished components. Less-reliable parts, however, are usually cheaper. Selling the government defective or substandard equipment is also prevalent.

The Department of Defense generally has two options in awarding contracts. “Fixed-price” contracts pay contractors a pre-established amount for goods and services, regardless of the company’s actual costs. “Cost-plus” contracts rely on a fixed amount, too, but also include a provision to cover a percentage of the contractor’s costs.

When a contractor is awarded both types of contract, they have a strong incentive to shift costs from their “fixed” contract to the “cost-plus” contract, thus off-setting costs from both projects. This fraudulent scheme, known colloquially as “cross-charging,” can also be used to offset the costs of similar defense projects undertaken for a private company or foreign government.

Needless to say, “cost-plus” contracts also create the incentive to simply inflate costs and increase profits.

When your job is to procure the most complex military systems in the world, finding a market can be hard. Many sophisticated defense technologies are manufactured by a single producer, leaving the government with no rationalizing mechanism (e.g. competition) to ensure a fair price. The Truthful Cost or Pricing Data Act (enacted in 1962 as the Truth in Negotiations Act) steps in for these single-source situations, granting the government access to a contractor’s cost data. Inflating one’s costs can be an enticing proposition when you know that no other company can outbid you for the work.

Overcharging the government for goods or services is often illegal, since most contracts signed with federal agencies require that manufacturers and distributors offer the “best price.”

Below, you’ll find a few examples of government fraud that generally rest outside the domains of healthcare and defense:

Needless to say, we’ve only scratched the surface of government fraud in these examples.

Some claims are explicitly left out of the False Claims Act, depending on who is being sued or how the information was acquired:

There is one major exception that last rule, known colloquially as the original source exception. Despite having been publicly disclosed already, false claims can still give rise to a viable qui tam lawsuit if the case’s relator can be deemed an “original source” of that information. In this context, “original source” usually means the relator has direct knowledge of the fraud, independent of any publicly-disclosed information, and they are the first person to tip off the government.

Citizens with knowledge of fraudulent activity that impacts the government’s coffers enter a federal court, submitting a legal complaint that presents their allegations in summary. A second document, or memorandum, is provided to federal investigators, but not the court, providing a full factual account of the fraud and any supporting documents necessary for substantiation.

This evidence is all-important; cases hinge on the amount and quality of proof that is provided to the government. None of these documents are disclosed to the case’s defendant, the individual or business who has been accused of defrauding the government. Even the legal complaint that kicks off a qui tam litigation is kept “under seal” for at least six months.

Only the government is allowed to access or view the complaint. The public can’t see it, either. In fact, qui tam complaints must be filed in camera – in a private manner with a federal judge. After filing their complaint, relators are sworn to secrecy; letting a detail enter the public domain can lead to immediate dismissal.

Filing a False Claims lawsuit triggers a federal investigation, as Justice Department officials attempt to find corroboration for the allegations of fraud. The 60-day period during which complaints must be kept under seal ensures that the defendant does not alter their business practices or attempt to destroy evidence.

In practice, the government almost always asks for the 60-day period to be extended. Judges almost uniformly grant this request. Federal investigations usually take a long time. Years can pass before the government decides whether or not there is sufficient evidence to support federal intervention.

The federal government “intervenes” in a small minority of qui tam lawsuits. When it does, investigation and litigation efforts are turned over to the Justice Department. Relators remain parties in the case (“co-plaintiffs”) and their attorneys can play a limited role in court proceedings. The decision to settle or dismiss the case, however, is now completely out of the relator’s control.

In some sense, it was always this way. People who file whistleblower lawsuits do so on behalf of the government; the federal government is always the lawsuit’s “real party in interest” – the entity with the legal right to enforce their claims against someone else.

When the government decides to stay out of the case, relators have the option of continuing on their own. With the full force of America’s courts behind them, relators can subpoena witnesses and access corporate and government documents to develop evidence.

Meanwhile, the False Claims Act gives the government the opportunity to intervene at a later date, if the relator’s investigation turns up evidence worth pursuing on a larger scale. The case, though, proceeds much like any civil lawsuit, with settlement negotiations and, possibly, a court trial.

For obvious reasons, the chances of success drop significantly when the government decides not to intervene, but the potential rewards grow as well. Whistleblowers who are successful in recovering federal money are (almost) always entitled to a portion of that recovery.

This incentive, or “reward,” can be quite substantial. In 1986, Congress even amended the False Claims Act to sweeten the pot, granting some relators far more than the 10% of recovered dollars that served as an absolute maximum in previous years. How much any one relator will be awarded is ultimately up to a judge, but federal law provides guidelines from which most judges are loath to deviate. The amount depends on how much effort the relator expended in securing the government’s money:

Within these ranges, judges have discretion, granting bigger awards to relators who shouldered more of the investigative burden. They can also reduce a reward when it becomes clear that the relator, despite having acted honorably, was involved in the fraud at issue. It’s notable, however, that people who participated in fraud against the government can themselves secure compensation by stepping forward and assisting an investigation – unless, that is, they are convicted of a crime related to the fraud. In that case, the relator will be dismissed as a party to the case and shut out of any subsequent recovery.

Most successful relators are also awarded compensation for their attorney’s fees.

The False Claims Act’s anti-retaliation provision can also play a part in determining awards or, alternatively, form the basis for a separate legal action.

Retaliation here is defined broadly; in the law’s own words, people who file whistleblower lawsuits are protected from being “discharged, demoted, suspended, threatened, harassed or in any other manner discriminated against in the terms and conditions of employment.”

When an employer retaliates against an employee who has exercised their right to file a qui tam lawsuit, the employee becomes entitled to double damages. The point is to make the employee “whole” again, returning them to the position they occupied before the retaliation occurred. As a result, the damages awarded in a False Claims Act retaliation lawsuit can vary from reinstatement in one’s job, re-promotion or double the back pay owed (plus interest).

Embedded in the False Claims Act is a deadline, a time limit for filing lawsuits under the Act. This is known as the law’s “statute of limitations.” The statute of limitations for qui tam lawsuits is either

whichever dates come later. No lawsuit can be filed more than 10 years after the legal violation.

info@legalherald.com

info@legalherald.com